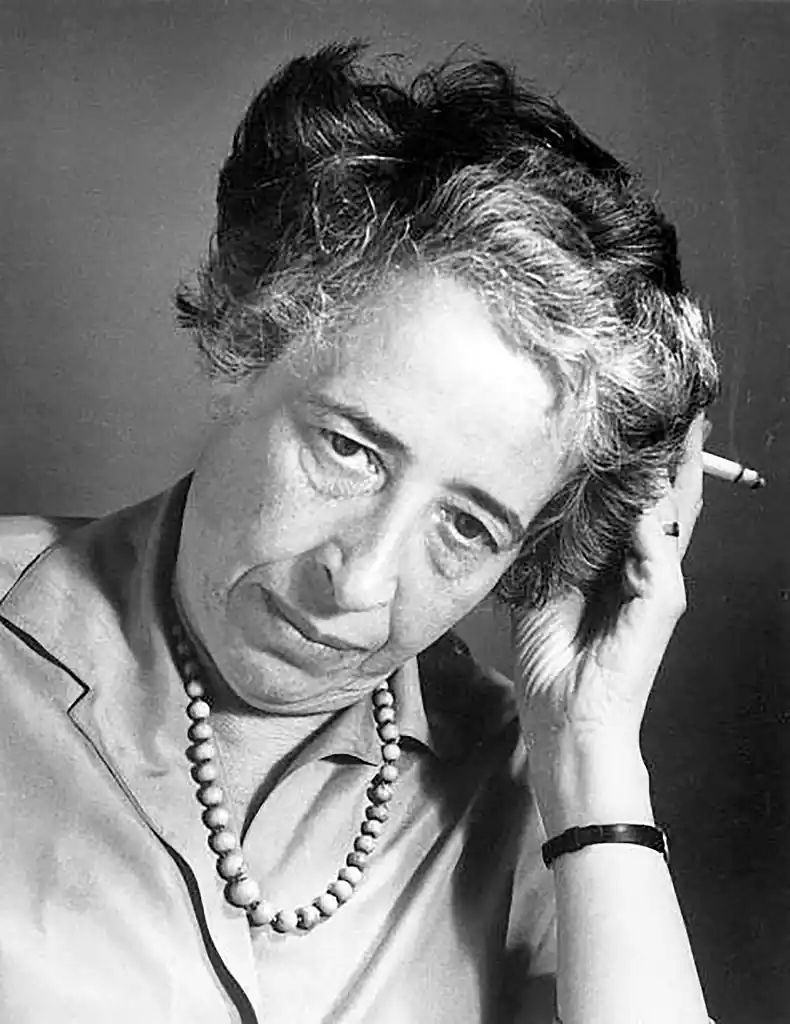

In an interview given to Günter Gaus, released on 28 October 1964 in West Germany under the title Zur Person, Hannah Arendt – the smoke curling off the tip of her cigarette – says that she wants to “look at politics with an eye unclouded with the philosophy”. There is a tension between (wo)man as a thinking being and (wo)man as an acting being that seems to be of particular importance when applied to Arendt’s intellectual voyage from the “enclosed garden” of philosophy to the public sphere of political theory. In this essay, my major focus is on the tension produced by the dynamics of opposing[1] in developing philosophical argumentation in the course of philosophy-doing. The feeling of that complex tension becomes existentially important for Arendt. When I say “existentially” I mean two different, yet connected things. First, I refer to the importance of the “need to understand” for Arendt, as exemplified in the sentence in the interview where she remembers how after having discovered Kant in her parents’ house library – she has just one alternative: either to study philosophy, or to jump in the river. Propelled by the need to understand philosophy, the fourteen-year-old child Hannah has become a compulsive reader, constructing herself as an existential subject whose very existence first presented itself as a riddle and a task to solve, then – in the formative university years, under the influence of Jaspers – the same subject constructed itself as a problem, enabling existential philosophy to become the basis for Arendt’s theory of action.

As Bruno Latour said in Politics of Nature, “Scientists argue among themselves about things that they cause to speak, and they add their own debates to those of the politicians. If this addition has rarely been visible, it is because it has taken place—and still takes place—elsewhere, inside the laboratory, behind closed doors, before the researchers intervene as experts in the public debate by reading in one voice the unanimous text of a resolution on the state of the art” (Latour 2004, 63-64). What is the nature of that uncanny “we” that exists across Latourian networks that are simultaneously real, like nature, narrated like discourse, and collective, like society? (See Latour 1997, 6-7). Is it possible for an “I” to get re-created across contemporary networks? If the answer is yes, then at what stake? How should an individual “I” perform nowadays, and what makes its performance valuable? Is there a daimonian code to the social language that makes the voice of an “I” sound like a “valid personality” to another “I”? Is there a special type of spectating necessary for an Arendtian “space of appearance” (Arendt 1998 [1958],199) to be brought to existence in the contemporary world? Has the nature of witnessing the reality of the public sphere changed since Arendt’s times, and how much equality and distinction is contained in the “plurality” of individuals who judge the value of the public sphere while participating in it?

Here I propose differentiating phenomenological participation in the mutually co-created actor-spectator “space of appearance” as the internal, individual space of ethical re-creation of the subject (Arendt’s internal polis that goes wherever a person goes), from historically actualized performances in the public sphere. The performative virtuosity of freedom inherited from the ancient Greek type of democracy, is seen in Arendt as a performance of public disclosing of shared values. Let me use a metaphor from the practice of performing arts: if there is some improvisation on agora, it is structured. Arendt’s concept of plurality is a dramaturgically (and narratologically) constrained freedom. The virtuosity of freedom is a performance of shared narratives and dramaturgical scripts. Even if Arendt notices some kind of thinking-doing related to the unstructured risk of historical participation in the public sphere, it does not seem important to her. Performing philosophy in the public sphere becomes politically relevant for Arendt only in connection to Jaspers’ “boundary situations” (Jaspers 1973) which are then re-thought as existentially heightened moments in the shared collective narrative. Rehabilitating politics among thinkers is important for Arendt but it does not imply overcoming the old tension between thinking and doing. Arendt insists on showing how the act of thinking in “dark times” changes the very essence of philosophy by establishing a new possibility of balancing the otherwise opposing tendencies of belonging to and withdrawing from. Again, unstructured thinking-doing is politically relevant only in connection to the ”boundary situation” that has disrupted the warp and the weft of a shared narrative texture of what Arendt perceives as the community constituted by memory. The most drastic example of it is the challenge of philosophizing as thinking-doing in the times of the Holocaust.

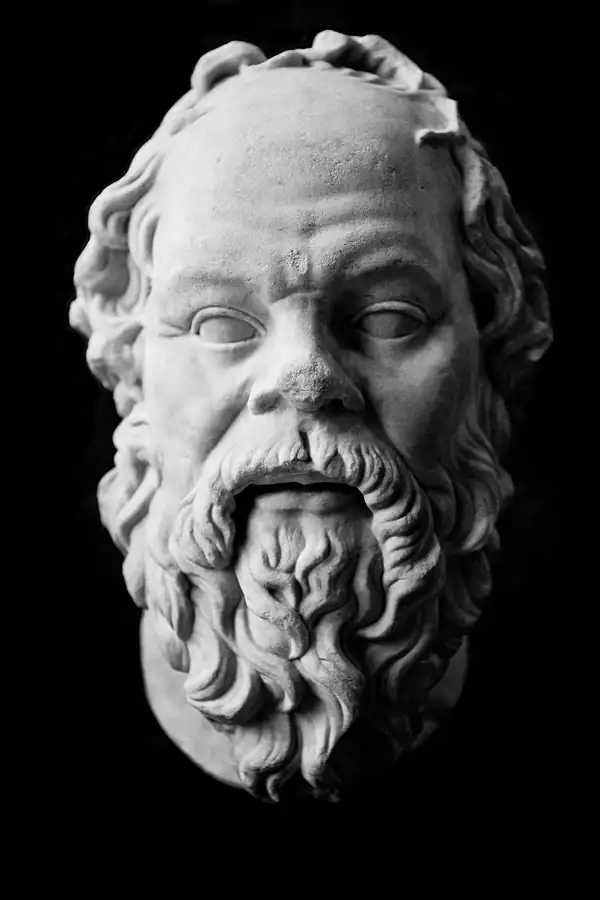

There is a dramaturgical potential in Plato’s philosophical thinking where the re-creation of Socrates’ persona always remains in an intrinsically motivating relationship with the most intimate process of Plato’s discovery of his own philosophical Who. I see this Platonian Who – invented from the tension between living in the polis and dwelling in the “neighborhood of those things that are forever” – as an important component in the development of Arendt’s concept of Who versus What.

When confronted with Plato’s ambiguities – one could not escape noticing that there is something that remains unresolved by his dialectics. I would – though tentatively – define that ambiguity as a surplus of artistic value in Plato’s art of the experimental. Aristotelian technê of peirastics (from peirastikê = experimental) includes the process of wandering – because, in order to get clear of difficulties, one should first engage in the free play of thought that implies the solution of the previous difficulties, as stated in Metaphysics (see Aristotle, 1991 Book III (B) 995a24-995b4). The nature of the art of the experimental, however, is different from Plato and in Aristotle. Aristotle’s thinker-wanderer has to experience getting lost before eventually finding the well-directed path. Aristotelian aporia tends to be resolved by tracing the path out of difficulty, while Plato’s aporia frequently gives the impression of staying in the realm of ambiguity. Plato’s style of proliferating aporias produces a dialectical surplus of value. And that value – quite surprisingly – is of the artistic kind. How does the surplus of artistic value in Plato’s style contribute – if it contributes at all – to the knowledge of the knowledgeable – the epistêmê of gnoristics (from gnôristikê = knowledgeable)?

Perhaps there is a need to think anew about the difference in the interpretation of peirastic wandering connected to the treatment of aporias in Plato and in Aristotle. Plato’s Socrates says in Theaetetus (Plato 1922, 155d) that “wonder is the only beginning of philosophy”. Wonder is provoked by aporias – claims Aristotle in Metaphysics (see Aristotle Book I (A) 982b11-982b28; 983a13-983a21). People are amazed at the possibility that things are as they are. They wonder at the fact that something they thought to be such as such is actually different from what they thought. Aristotelian thaumazein disappears when somebody learns something. The capacity to be amazed is connected to thinking, but people start to seek knowledge only when their economic needs are satisfied.

Arendt points to “the philosophical shock” experienced by “all great philosophers” (like Socrates) who are willing to endure “the pathos of wonder” when they come into contact with the majority of people who either “know nothing of the pathos of “wander”, or who “refuse to endure it” (see Arendt 2005, 33). Nominally following Plato’s footprints in the dust of antiquity, Arendt is actually having in mind the entire platonic legacy of the concept of thaumazein. The same stands for the concept of pathos: different meanings of pathos can be distracted from different “voices” in Socratic dialogues. It was impossible for Arendt to rely solely on Plato, without being aware of multiple layers of meaning attributed to that concept across the historical line of philosophy that goes from Plato to Aristotle, across Hegel, and Kierkegaard to Heidegger. With Heidegger’s interpretation of Aristotle’s pathos in Basic Concepts of Aristotelian Philosophy – the same line of interpretation goes all the way back to classical antiquity.

Before analyzing Arendt’s conceptual blending of pathos and wonder, I have to deal with several problems connected to that line of philosophical heritage. Let me first introduce a couple of new working terms – concept identity and etymological mythos – in order to claim that the rhetoric of the unsaid pre-philosophical identity of Aristotle’s and Plato’s concepts is in their etymological mythos. I would like to propose a hypothesis that the unsaid identity of Plato’s and Aristotle’s concepts has given historical grounding to the categories of being in Heidegger. Heidegger’s scholarly most scrupulous philological excavating of that “mythos” in the early twenties was a way of giving a historical grounding to the unsaid in the Greek thinkers.

The fact that there is no single meaning of pathos in Aristotle has been commented on by classical philologists before and after Heidegger (See e.g. Bonitz, 1870), but Heidegger’s interest in identifying various types of conceptual ambiguity and the coming to be of Aristotelian basic concepts – has remained unique in its (auto)pedagogical rigor. This rigor concerns both mediating “the real”, un-Latinized Aristotle to students, and building a foundation for Heidegger’s own concepts presented in Sein und Zeit. In such a way, Heidegger’s phenomenological reading into Aristotle’s metaphysics is an activity connected to the unsaid in the saying of another philosopher. But the unsaid, “das Ungesagte” (see Kant 1962 [1929] 207) in Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, is unconcealed in its dialogical quality of confrontation, in Auseinandersetzung as an intrinsic setting-in-opposition. It seems to me, though, that it is not possible to explain “das Ungesagte” only in terms of its confrontational dynamics: as a “lover’s quarrel” in the service of truth. It has also to do with the creative potential of language and the logic of translation connected to the path of living. In both approaches to the unsaid, there is an aspect of tension-showing and showing-in-tension. Heidegger defined it, writing of Cézanne, as “tension of emerging and not emerging to the surface” (quoted in Petzet 1993, 143). Coming to the surface of the painter’s canvas, this tension becomes „onefold, transformed into a mysterious identity“. In a letter to the poet René Char, Heidegger says first that his own pathway of thinking responds in its own way to Cézanne’s, and then he makes a rhetorical question concerning Cézanne’s work: „Is there shown here a pathway that opens onto a belonging-together of poet and thinker?” This cryptic question is an answer to the painter’s simple claim: “I love the harmonious blending of shapes in my fatherland” (quoted in Petzet 1993, 144, marked by S.P.). The artist’s naïve mentioning of “blending” has obviously succeeded in affecting the philosopher’s mind. It happened subliminally, somewhere below the threshold of sensation and consciousness, invoking “Plato” in Heidegger with a sudden flesh of understanding. “Plato” is a hypothetical thing, a dynamical model of a persona fulfilling certain dramaturgical dynamics in a particular historical-philosophical niche in human geography. But this “Plato” invoked in Heidegger is also an entire body of Plato’s work open to Heidegger in its deadly serious hide-and-seek playfulness. It functions as a whole, and at the same time, as a fragment – just like the following fragment from Plato’s /Pseudo-Platonic Seventh Letter:

“After much effort, like names, definitions, sights, and other data of sense, are brought into contact and friction one with another, in the course of scrutiny and kindly testing by men who proceed by a question and answer without ill will, with a sudden flash there shines forth understanding about every problem and an intelligence whose efforts reach the furthest limits of human powers” (Plato 2014, 42, 344c).

Heidegger is remembered by his friends as a “real” person sitting on a particular spot in the “real” landscape. He is depicted in their memory as sitting in silent contemplation of nature – deeply involved in a timeless moment of co-creatively tensed stasis. This silent moment of an unmeasurable duration seems dramaturgically appropriate for blending Cézanne’s and Heidegger’s paths in an act of making what Heidegger named a “mysterious identity”. Cézanne is a “poet” for as much as his artistic creativity derives its “mysticism” from the ancient, pre-Platonic concept of poíēsis. The joined identity of poet and thinker is based on the supposedly original link between the notions of poiesis and noein as explained by Heidegger in his lecture titled An Introduction to Metaphysics delivered in 1935.

Much like Heidegger’s “Plato” – that “Heidegger” we “know” now (when occasionally engaging in a serious play with his philosophical system of thought), does not exist, except in his dramaturgically functional persona that is coming to be each time one of his concepts becomes active relatively to another concept in the playground of human ideas. It is in such moments that Heidegger becomes someone relatively to somebody else. Let me use an analogy from physics: a “mysterious identity” of “Cézanne” and “Heidegger”, is an energy released as an outcome of the work of Heidegger’s system of thought. Cézanne is a “poet” insofar as his artistic creativity derives its “mysticism” from the ancient concept of poíēsis . This energy could also be proof of the fact that Heidegger’s philosophical system is able to do work. Of course, it is preferable in a philosophical context, that this work gets detected and identified by the philosopher himself, then potentially by other philosophers participating in an exchange with his system. The energy – shifted from one system to another – is a scalar quantity; it is abstract and cannot always be perceived, but it is given meaning through some sort of insight, let us call it provisionally – philosophical calculation. Each philosophical system has its potential energy (it has its philosophical force field and its quantity in a field, some sort of a philosophical charge). Each philosophical system also has its kinetic energy connected to the motion of philosophical concepts (except that the flow of concepts as philosophical charges could not be illustrated simply on the example of the bulk flow as in electrical energy, because this flow-like movement gains in complexity as it engages in cognitive dynamics).

Heidegger’s system of thought maintains a highly charged philosophical relationship to Plato’s Lehre as his unique system of thought: “Die Lehre eines Denkers ist das in seinem Sagen Ungesagte” (see Heidegger 1947: 5). But it is a lot more than a doctrine of a particular thinker because philosophical systems are not merely human expert systems capable of problem-solving. Heidegger recognizes hidden lawful regularities in that which is unsaid in Plato’s saying. However, that law gets realized in Dasein only in the intervening space where Plato’s persona gets charged into becoming in relation to Heidegger’s persona. The play-space of that activity – Heidegger’s “Spiel-Raum” – is being created by imagination.

But what is the role of imagination in establishing what was interpreted as a product of dynamic tension between the poles existing in a joint intervention space? To what extent is Heidegger’s Lehre charged by the unsaid in Theaetetus: concretely by the movement of Heraclitus’ idea of a hidden harmony that underlies Plato’s philosophical system, and by the role of this concept in discharging energy from confrontation with Protagoras?

Heraclitus’ concept of a “hidden harmony” as a stable ground beyond the flux of natural change is important for Plato. That is why he makes a methodologically imaginative decision: he uses Socrates’ dramatis persona to imbed Heraclitan’s postulate of radical flux into Protagoras’ system of thought by treating that postulate as a Protagoras’ „secret doctrine“. Plato’s theory of perception developed in Theaetetus is extremely interesting when re-read in the context of contemporary action-based theories of perception. Things are not stable entities but dynamical units: we cannot say that they “are” because they are always “coming to be”. The singularity of the perceiver, the perceived, and the perception is achieved in each and every particular event of perception. The process of Platonian “coming to be” is a result of a three-fold dynamism: movement, change and blending. Here I come to the point: Cézanne’s innocent remark that he loves the harmonious blending of shapes served as a subliminal stimuli that instigated a memory recall in the philosopher: Heidegger remembered Plato’s Theaetetus. As quoted before, Heidegger sees a pathway that opens onto a belonging together of poet and thinker in the tension that becomes “onefold” and transforms itself into a mysterious identity. The imaginative act of disclosing the hidden, and saying what remained unsaid in another person’s system of thought is conceptually linked to an emergently creative potential of poíēsis – to Heidegger’s concept of “bringing forth into presence”. Needless to say that the “mystical” aspect of blending the identity of a poet and a thinker connected to poíēsis had been most famously introduced in Plato’s Symposium by Diotima. The pre-Socratic Eros Phanes is the very first, primordial force – the Prôtogenos of creation in the Orphic cosmogony: the one that, according to the etymological mythos of his name, has been responsible for bringing all there is forth into the light of presence. (From Greek – phanes, from phainein – “bring to light, cause to appear, show”; from phainestai – “to appear”). I assume that Heidegger’s poíēsis as the modus of disclosure, and as the original place where the Being discloses itself – is founded in ancient Greek etymological mythos.

One of the aims of this little exercise in the practice of philosophizing is in pointing to the concealed “mystical identity” of Heidegger and Arendt. I do not see their joined, dynamically tensed identity on the level of Heidegger’s influences on Arendt’s philosophical formation, but in what they both (differently and on different strata of philosophical insight) do not ʺsee” in themselves. The blind spot, and the unsaid of what they are saying, are made to appear by Plato’s “Diotima” who assumes a daimonic function in re-Platonizing their anti-Platonic claims. Daimonic functionality – as I use it here – is developed on the basis of Arendt’s reconceptualization of the ancient concept of daimon. I use that functionality here as a “tool” in the analysis of the development of some of Arendt’s key notions which I see as constructed by mutually opposing kinetic energies of standing in relation to and diverging from Plato.

Arendt’s modern transfiguration of Plato’s notion of pathos – at least as I see it – is in the public exposure to the bright light of the constant presence of others. Unlike Plato’s pathos – as something which is endured in the wonder at that which is as it is (see Arendt 2005, 32-33), Arendt‘s pathos is in revealing “who” she really is to the fixing eye of the other in the open space of appearance:

In acting and speaking, men show who they are, reveal actively their unique personal identities, and thus make their appearance in the human world, while their physical identities appear without any activity of their own in the unique shape of the body and the sound of the voice. The disclosure of ‘who’ in contradiction to ‘what’ somebody is – his qualities, gifts, talents, and shortcomings, which he may display or hide – is implicit in everything somebody says and does. It can be hidden only in complete silence and perfect passivity, but its disclosure can almost never be achieved as a willful purpose, as though one possessed and could dispose of his “who” in the same manner he has and can dispose of his qualities. On the contrary, it is more than likely that the ‘who’, which appears so clearly and unmistakably to others, remains hidden from the person himself, like the daimon in Greek religion who accompanies each man throughout his life, always looking over his shoulder from behind and thus visible to those he encounters (Arendt 1998 [1958], 179-189).

Although she personally opted for the pathos of exposure in the sphere of appearance, Arendt claims that the philosopher’s experience of the eternal can occur only outside the realm of human affairs and outside of plurality of men, as a potential way to immortality. She exemplifies that particular type of experience in Plato’s arrheton as the “unspeakable”, and Aristotle’s aneu logon as “without word”, adding to it the concept developed later: the paradoxical nunc stans – the “standing now” (see Arendt 1998: 20). I have some reservations about Arendt’s interpretation of these ancient notions primarily because arrheton is the notion that historically has to do with the concrete rituals practiced in Mysteries connected with Demeter at Eleusis, Arcadia and Messenia. These rituals as such have contributed to the construction of social reality in ancient Greece. The ineffable in this ritual was not – as in later apophatic religions – connected to the via negativa approach to attributes of God, but rather to the aspect of “inexpressibility” of something that can be known only by experiencing it first hand, and not in the narrated form. The taboo implicit in the concept of arrheton concerns the act of narrating about the performance of the “pure” union of Demeter as mother-goddess with the horse-shaped Poseidon. Arendt’s interpretation is weighted with the Western Christian religious tradition of interpreting Plato and Aristotle. On the other hand, it is worthwhile mentioning that the theological concept of the ineffable as an attribute of God who is described by way of denial as – ineffable, inconceivable, and incomprehensible –is considered the central doctrine of the orthodox Christian church whose tradition reaches back to Clement of Alexandria. There is an element of exclusivity in the ritual practiced in Mysteries, but it is covered by another term – apporheton – in the sense of something concerning the performance of ritual which is not accessible to everybody, but only to initiates. Arrheton and aporrheton – the inexpressible and the inaccessible in talk (in lexis) and in action (in praxis) – are socially coded roles of transgression. They should be perceived as functional elements with a special place in the ritual syntax of the Demeter-centered ritualistic practice whose dynamics correspond to the calendar of public festivities.

The way Arendt makes the conceptual blending of pathos and wonder is taken for granted – both by Arendt herself and by her interpreters. These concepts are connected to the dialectically founded aporistic method used by Plato and Aristotle. The verb aporein is etymologically linked to the experience of coming to difficulty in the passage. It seems to me that this term as such does not only establish associative links with the social context in which a human subject can experience difficulties but that it also points to the organization of movement in space. I would like to suggest that the logical disjunction, the concept of an impasse in thinking, stays most “naturally” connected to the particular spatial dynamics of polis; to a concrete dead-end in a street that every human being can remember, and to a plethora of concrete factors of human geography (natural, social, economic, cultural, historical and political) that condition and control movement in a polis. The most ”natural” way to put aporistic method to use in the city and for the city was to simulate its functionality in the dialogical encounter of “real” persons depicted as dramatis personae. Methodological use of Socrates as dramatis persona in Plato’s dialectics is connected to the etymology of the compound diaporein – “to run through the difficulty from one end to the other”. The diaporia – as an examination of the opposed – etymologically “invokes” wandering: an irregular movement that also contains a bitter taste of some toing and froing in everyday life. The aporistic “no way” does not necessarily bring the process of “running through the difficulty from one end to the other” to a satisfactory solution. Socratic dialogues do not necessarily offer euporia as a final discovery. I am prone to think that in Plato’s dialogues dead-end becomes the reality of movement. Socrates’ persona sometimes stays in wonder, speechless, amazed by the euporistic reality of movement in the space of Athenian human geography. This is where Plato’s aporistic method produces that surplus of artistic value I had already identified earlier in the text. The dynamical potential and the energy inherent in the reality of movement typical of diaporeatic “running through the difficulty from one end to the other”; the ambiguity of what remains unresolved by dialectics – ultimately gets resolved in Plato’s art of the experimental. This experimental technê of philosophizing (which should be seen in separation from Plato’s insight into the limitations of technê as a wisdom model) develops its unique dramaturgical logic which concludes the dynamics of the formation of Socrates’ dramatis persona in the performance of his death. The creating of persona, however, has never been modeled as a process that is essentially incomplete in its liveliness, but rather as an activity – dramaturgically pre-conceived. This dramaturgically complete activity is on the level of its performance in the polis – (self)spectated as thaumazein. Let me explain that: the wonder of the protagonist of this moment (and the way his disciples wonder in connection to the impasse in the aporia of Socrates’ life) – is located in the Athenian polis, and its energy could be released only in connection to the particular spot on the map of Greek human geography. What I suggest here is that the unsettling, mysterious nature of energy released in the Platonic diaporeatic activity – perceived here as the dead-end activity becoming the reality of movement – precedes the Aristotelian concept of enérgeia. What presents itself as a possible common ground between Plato’s mysterious spin-off energy of dialectics, and the concept of enérgeia introduced and elaborated by Aristotle – remains in the domain of the art of the experimental – in the technê of peirastics. However, Plato’s methodology used in Socratic dialogues transcends the aporistic methodology seen only as a tool of dialectics, and in this way, it creates significant tension in Platonic thought. Perhaps I can elucidate upon the nature of this “tension” in relation to the systems science – explaining it as energy generated by a system as it negotiates differences. The energy generated by the system of Plato’s philosophizing is generated by wondering at the complex dynamics of negotiation. My interpretation of the dead-end energy dynamics of wonder as caused by diaporeatic activity is very much different from Arendt’s interpretation (and critique) of Plato’s “admiring wonder” which initially shows the influence of Heidegger’s interpretation of Plato’s “wonder:

“The Platonic wonder, the initial shock that sends the philosopher on his way, was received in our own time when Heidegger, in 1929, concluded a lecture entitled What is Metaphysics? with the words already cited, ‘Why is there anything at all and not rather, nothing? and called this the basic question of metaphysics’’ (Arendt 1981, 150).

Departing from this metaphysical question that asks about the cosmological totality of entities, Heidegger is able to pose another question essential for the development of his fundamental ontology – “What does ‘being’ mean?”. By asking that, he brings back the “forgotten” question of the meaning of being, back to Plato, and at the same time distances himself from traditional ontologies whose ontic focus is on the factual of entities and not on their phenomenal existence and the meaning of being. It seems to me that Arendt does not see in Plato what Heidegger wants to bring back to him as his long-forgotten “unsaid”. Arendt is not so much interested in inherently social aspects of Dasein, and even less in exploring the “past” of that concept in Husserl’s concept of transcendental consciousness. She finds Heidegger’s Being-in-the-world (In-der-Welt-sein) and the connected concept of taking care more inspiring for the development of her own doctrine of thinking. Arendt’s priority is the actual problem of how to live in the world:

“Admiring wonder conceived as the starting point of philosophy leaves no place for the factual existence of disharmony, of ugliness, and finally of evil. No Platonic dialogue deals with the question of evil. Only in the Parmenides does he show concern about the consequence that the understandable existence of hideous things and ugly deeds is bound to have for his doctrine of ideas” (Arendt 1981, 151).

Arendt’s political theory is operating in everydayness. Her concept of natality is close to the concept of beginning (Anfang) in Heidegger’s philosophy, but Arendt uses Saint Augustine’s initium in order to obstruct the Heideggerian need to re-enact and re-discover. She does it by use of Augustinian refutation of the philosophers’ cyclical time concepts inasmuch as novelty could not occur in cycles (see Arendt 1981, 108-109). The heritage of Plato in Saint Augustine, and of Augustine in Heidegger and in Arendt, is a valuable, interesting, and already well-covered topic with some room left for renewed studying, but the aim and the format of this text do not permit me to deal with it.

Arendt is making her critique of Plato by counterbalancing pre-Socratic philosophical thoughts with Plato’s thoughts in which she follows Heidegger’s example. However, without Heidegger’s consistency in tracing back ancient Greek metaphysics into pre-Socratic proto-phenomenology and tracing it forward into his own system of thinking, Arendt’s willingness to see, but unwillingness to acknowledge that most of the supposedly anti-Platonic arguments have been already identified as problematic in Plato’s philosophical dramaturgy – is specious, and occasionally mistaken. All pre-Socratic philosophers that Arendt mentions in her critique of Plato – including Socrates himself – have already been given voice in Socratic dialogues. Plato’s dramaturgically shrewd practice of going beyond dialectics (the creation of personae, and his diaporeatic running through the difficulty from one end to the other) goes beyond dialectics as a tool in order to point to the same law that gets realized in Heideggerian Dasein. The law manifests itself in the intervening space where Plato’s persona gets charged into becoming in relation to other personae in his Socratic dialogues.

In The Life of the Mind, and elsewhere, Arendt mentions the obvious, namely, that there is no sharp dividing line in what is authentically Socratic and the philosophy taught by Plato (see Arendt 1981, 169). It is worthwhile to note that Arendt seems to be irritated by Plato’s aporistic method:

“None of the logoi, the arguments; ever stay put, they move around. And because Socrates, asking questions to which he does not know the answers, sets them in motion, once the statement have come full circle, it is usually Socrates who cheerfully proposes to start all over again and inquire what justice or piety or knowledge or happiness are” (Arendt 1981, 169-170).

Arendt’s negative emotional reaction spills over the body of her text into the note where she elaborates upon already been said:

“The frequent notion that Socrates tries to lead his interlocutor with his question to certain results of which he is convinced in advance – like a clever professor with his students – seems to be entirely mistaken even if it is as ingeniously qualified as in Vlastos essay (…), in which he suggests that Socrates wanted the other ‘to find … out for himself”, as in Meno, which however is not aporetic. (…) The most one could say is that Socrates wanted his partners in the dialogue to be as perplexed as he was” (Arendt, 1981, 236).

When transferred to the surface of everydayness where the factual existence of disharmony, of ugliness, and evil, appear in their banality – the speechless wonder of Plato’s “Socrates” and Heidegger’s “Plato” loses its deep meaning. This deepness of the meaning of wonder has been and remained to be recognized from the times of antiquity till today in offering the unsaid of what was said to another thinking being. It manifests itself in opening the energy of the unwanted, painful, and concealed unsaid for somebody else’s performance of what could be named from the modern and contemporary perspective as phenomenological hermeneutics.

Arendt’s concept of the “banality of evil”, as explained in Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil in 1963, is not seen in her political theory with reference to the concept of classical “wonder”. It is a great pity – because some of the misinterpretations of her syntagma “banality of evil” are based on not knowing the entire opus of Arendt where she develops her moral theory from Kant. The concept of the normative morality of people makes ordinary people too easily succumb to group selfishness in cases when there is a surplus of normative morality in the group. Arendt’s seemingly simple, but actually complex concept of the “banality of evil” has to be read not only in connection with Nazi totalitarianism and her definition of rationally unmotivated “absolute evil” as explained in The Origins of Totalitarianism, but also in the broader context of Arendt’s trinity of power-strength-authority, with an adjacent problem of violence that remained in her theory without one obvious meaning (see Arendt 1951). Every concrete example of Kant’s “hypothetical imperative”, where somebody is led by the will to achieve some end, becomes morally doubtful depending on how this end is willed. In Kant’s normative ethics, good and wrong are not functions of good and evil, and that introduces some problems in Arendt’s own theory because in analyzing the factual examples of the existence of evil in human society, Arendt had to acknowledge that moral acts do not always come as results of reasoned deliberations. The notion of “plurality” is one of Arendt’s key notions that – connected to her definition of “the space of appearance” – has become one of the most important interpretations of the public sphere in contemporary political theory. But Arendt’s “plurality” introduced in The Human Condition has been conceived by uprooting the notion of “spectator” from the context of Kant’s aesthetic theory and planting it into the field of political theory where it advanced and expanded, causing in the process of its development some potential difficulties. The kantian spectator is an active agent in perception capable of determining the object in its motion and rest not from the object itself but by the act of spectating. Spectating in Kant is the way an object is brought to existence for the one who observes it due to the observer’s perception. Arendt is interested in Kant’s communicability of human sensations, but again – her intention is to see what could be the implications of that innate communicability when transferred to the public sphere as the sphere of appearance:

“The condition sine qua non for the existence of beautiful objects is communicability; the judgment of the spectator creates the space without which no such objects could appear at all. The public realm is constituted by the critic and the spectators and not by actor and fabricator; without the critical, judging faculty the doer or maker would be so isolated from the spectator that he would not even be perceived. Or to put it another way, still in Kantian terms: The very originality of the artist (or the very novelty of the actor) depends on his making himself understood by those who are not artists (actors). And while you can speak of genius in the singular because of his originality, you can never speak … in the same way of the spectator: spectators exist only in the plural. The spectator is not involved in the act, but he is always involved with his fellow spectators. He does not share the faculty of genius, originality, with the maker, or the faculty of the novelty of the actor; the faculty that they have in common is the faculty of judgment (Arendt 1981, 262-263).

The notion that every appearance is perceived by a plurality of spectators, has been developed by Arendt into the idea that plurality makes the cornerstone of the human condition where “men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world” (Arendt 1998 [1958]). Hannah Arendt’s never completed three-part project The Life of the Mind was initially conceived as a modern parallel to the three Critiques of Immanuel Kant. It was written in the period when she was also giving lectures on Kant. The tension between philosophers’ contemplation in the protected territory of their own minds, and active participation in the sphere of appearance, is felt by Arendt more like a point of divergence of two bifurcating paths, than a dynamical relation in a system of human affairs. Arendt is not just minding the gap between philosophy and politics, and in her own case insisting on a methodological separation between political philosophy and political theory – she is tormented by an almost irrational need to find the exact turning point on the historical line: the Wendepunkt in the history of philosophical thought from which nothing had been the same. She finds that point in Socrates’ death. In the text conceived in the 50s as a series of lectures grouped around the problem of action and thought after the French Revolution, Arendt wrought a lengthy paper entitled Philosophy and Politics, mostly analyzing the consequences of Socrates’ trial in the context of the supposed change in the self-perception of the role of philosophers in the society after Socrates’ death. Arendt published a shortened version of that text in Cahiers du Grif in 1986, but the version edited by Jerome Kahn and published in the book The Promise of Politics, has a simple title: it is named just Socraties. There is an editorial reason – as there are other deep reasons for opting for simplicity when it comes to Arendt’s treatment of the topic of the “gulf between politics and philosophy that opened historically with the trial and condemnation of Socrates” (see Arendt 2005, 6). But this is a topic that I cannot elaborate on further in this text, because it is nuanced and as such more appropriate for a book-length study.

“The spectacle of Socrates’ submitting his own doxa to the irresponsible opinion of the Athenians, and being outvoted by a majority” – says Arendt – “made Plato despise opinions and yearn for absolute standards” (Arendt 2005, 8). Almost the post-traumatic anguish of those who think in closeness to eternity is produced in contact with those who act but do not think without being first persuaded in what to think. However, the retreat of philosophers from the world of human affairs, and giving up of the political purposes in order to live in contemplation of the universal order – the choice of vita contemplativa in preference to vita activa in the polis – is not the spot of departure of two different paths, but rather a triple bifurcation which cannot be safely located on the historical timeline. The already mentioned tension between active participation in the sphere of appearance, on the one hand, and the sphere of contemplation as a safe house for post-Socratic philosophers, on the other hand – is apparently convincing and well-argued, but whenever the Kantian notion of spectator enters Arendt’s discourse, one can identify the third path of bifurcation: the path of spectators’ participation in the matters of polis.

Arendt’s analogy between theatrical events and political affairs shows a certain amount of unspoken conservativism and traditionalism both in aesthetics and in political theory. But it seems that Arendt is unaware of her blind spot. The spectator is not involved in the act, Arendt thinks, but he is always involved with his fellow spectators. The spectators’ action which takes place somewhere between the warp and the weft of the narrative of the community of memory – although, according to Arendt, direct in itself and unmediated by things and matter – is following the dramaturgy that is, I dare say, devoid of direct involvement in the dramaturgy of political actuality. The place of the self-indulging spectacle of social fellowship is dislocated from the space of political action. In modern times, the source of thinking which has always been, and still today remains in personal experience, gets obscured by what Arendt calls the “enlargement of the private”. (Arendt: 1998, 52). This enlargement gets manifested in modern enchantment with “small things”. What the public realm considers irrelevant, says Arendt, can have such an extraordinary and infectious charm that a whole people may adopt it as their way of life; without that reason changing its essentially private character (see Arendt: 1998: 52).

Arendt diagnosed and described with great precision this modern transfiguration of the realm of personal experience into the realm of the petit bonheur, but she also established a firm barrier, almost a sanitary cordon around “things that cannot withstand the implacable, bright light of the constant presence of others in the public scene” where “only what is considered to be relevant, worthy of being seen or heard, can be tolerated, so that the irrelevant becomes automatically a private matter” (Arendt 1998: 51). I am not sure that it makes sense at all in our age of informational entropy, and in the context of a highly mediatized and globalized world with blurred barriers between “private” and “public”, “relevant” and “irrelevant”, “true news” and “fake news”, and even between “falsely true news” and “falsely fake news”. There is a potential danger in Arendt’s belief in the relevance of the narratives created collectively over time by communities of memory. Let us suppose that there is such a thing as the Community whose legitimacy is derived from the mythos initiated in the first gathering; the kind of Community that comprises in one cross-temporal narrative all the stories of the dead and all the stories of the living, and represents the interests of the currently gathered fellowship of spectators. But how can one be sure that it is really the Community that stands behind the Storyteller who ventriloquizes the actor who then, in his turn enacts and represents the interest of the fellowship of spectators? How can we judge the authenticity of that narrative? The nature of witnessing the reality of the public sphere has changed considerably since Arendt’s times, and we now know that there is not enough equality and distinction contained in the “plurality” of individuals whose power of political engagement is either insignificant in scope, or arbitrarily violent. All that is the outcome of spectating the happening of events in the sphere of appearance, rather than meaningfully participating in the dynamics of the public field.

Commenting on Kant in her lectures, Arendt asks:

“How could ‘contemplative pleasure and inactive delight’ have anything to do with practice? Does that not conclusively prove that Kant, when he turned to the doctrinal business, had decided that his concern with the particular and contingent was a thing of the past and had been a somewhat marginal affair? And yet, we shall see that his final position on the French Revolution, an event that played a central role in his old age, when he waited with great impatience every day for the newspapers, was decided by his attitude of the mere spectator, of those ‘who are not engaged in the game themselves’ but only follow with it with ‘wishful, passionate participation, which certainly did not mean, least of all for Kant, that they now wanted to make a revolution; their sympathy arose from mere ‘contemplative pleasure and inactive delight’” (Arendt 1992, 17).

But Arendt was also apolitical in her intellectual beginnings. By moving her focus of interest from the realm of pure philosophical contemplation into the sphere of political theory – she had found herself on the other side of the barricade of the intellectual “pseudo-kingdom”. Arendt had found herself in the domain of the human plurality where she was free to enjoy spontaneity in initiating action and acting together. Having escaped Plato’s “tyranny of truth”, Arendt became actively involved in sharing the faculty of judgment with others in the joint space of appearance. Her interest in the spectacle of human affairs was deep and meaningful, but her theoretical openness to the new beginnings in the political dramaturgy (and her Kantian fascination with revolutions) was very far from the actual engagement in the “game”. Just like Kant, Hannah Arendt was a passionate participant.

[1] New concepts and new terminology introduced by the author, as well as emphasized sections connected to new terminology, are marked in italics. All Latin and Latinized Greek terms are also written in italics. Philosophical concepts and terminology of other authors are put under quotation marks and referenced. All metaphorical, “so-called” and alleged is put under quotation marks.

References

Arendt, Hannah. 1961 [1954]Between Past and Future. Six Exercises in Political Thought. New York: The Viking Press.

Arendt, Hannah. 1963.Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil . New York: Viking Press.

Arendt, Hannah. 1964. „Zur Person – Hannah Arendt“. Im Gespräch mit Günter Gaus“. In The Rosemberg Quaterly. October 28, 1964. ISSN: 2212-425X. Accessed May 15, 2022. http://rozenbergquarterly.com/hannah-arendt-zur-person/

Arendt, Hannah. 1951. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Arendt, Hannah. 1976[1951].The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovitch.

Arendt, Hannah. 1981. The Life of the Mind. One-volume Edition (Vols 1&2). San Diego, New York, London: A Harvest Book & Harcourt, Inc.

Arendt, Hannah. 1992. Lectures of Kant’s Political Philosophy. Chicago: Th University of Chicago Press.

Arendt, Hannah. 1998 [1958]. The Human Condition. Chicago & London. The University of Chicago Press.

Arendt, Hannah. 2005. The Promise of Politics. New York: Schocken Books.

Aristotle. 1991. “Metaphysics” In The Complete Works of Aristotle. The revised Oxford Translation. Vol. 2. Princeton, New Jersey: Bollingen Series LXXI 2 Princeton University Press

Bonitz, Herman. 1955.[1879]Index Aristotelicus. Graz: Akademische Druck-u Verlagsanstalt.

Heidegger, Martin. 1983.[ 1935]Einfuehrung In Die Metaphysik. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klosterman.

Heidegger, Martin. 1947. Platons Lehre von der Wahrheit. Bern: A Franckle AG.

Heidegger, Martin. 1965.[1929]Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics. Translated by James S. Churchill. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Heidegger, Martin. 1967[1927]. Sein und Zeit. Tuebingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag. Elfte, unferänderte Auflage.

Heidegger, Martin. 2009. Basic Concepts of Aristotelian Philosophy. Translated by Robert M. Metcalf and Mark B. Tanzer.

Jaspers, Karl. 1973. Philosophie II. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag.

Latour, Bruno. 1997. [1991]We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Latour, Bruno. 2004. Politics of Nature. How to Bring Sciences into Democracy. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England: Harvard University Press.

Petzet, Heinrich Wiegand, 1993. Encounters and dialogues with Martin Heidegger,1929-1976; translated by Parvis Emad and Kenneth Maly; with an introduction by Parvis Emad. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Plato. 1921. “Cratylus” In Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 12 1921. Translated by Harold N. Fowler. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Plato. 1921. “Theaetetus”. In Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 12. 1921. Translated by Harold N. Fowler. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Plato 2014. “Seventh Letter” In Harwar, John. 2014 [1932]The Platonic Epistles Translated with Introduction and Notes by John Harwar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sibila Petlevski

Sibila Petlevski, a full professor at the Academy of Dramatic Art, University of Zagreb; doctor of humanities and scholar in the fields of theatre aesthetics, performance studies, and interdisciplinary art research; the principal investigator of the international project “How Practice-led Research in Artistic Performance Can Contribute to Science” supported by the Croatian Science Foundation (2015-2019); member of the Advisory Board of Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems – INDECS Journal. Apart from her academic and scientific career, Petlevski is an internationally awarded novelist, poet and playwright.