ŽARKO PAIĆ: Hal Foster in his seminal analysis of the relationships between concepts of avant-garde and neo-avant-garde entitled, The Return of the Real: Art and Theory at the End of the Century (The MIT Press, Cambridge Massachusetts, London-New York, 1994) emphasized the difference between a return of an archaic form of art that bolster’s conservative tendencies in the present and return to a lost model of art made in order to displace customary ways of working. Put it simply: there are two paths of returns nowadays in contemporary arts in general, not only in visual arts but should be exactly the same also for contemporary literature and performative arts. The first one inherited from dialogue with the unbroken tradition of “generic styles” which belongs to historical avant-garde as Dadaism, Futurism, and Constructivism, and the second one intended to interrogate the whole complex of picture/image from a new perspective. In the series Against the day (see: De Man vov Viels, 2008) your position towards the possible answers to that questions were articulated in-between the accumulation of memory and the archeology of memory. Can we ever return to the experience of the image as a trauma of the Real?

LUC TUYMANS: Body of works I had already made by now as much more damaging than what Richter managed with his entire oeuvre. How am I to take this quote as an insult or a compliment? I think neither one of them since quotes like this posted on the Internet are mostly totally out of context. What does transpire though is Hal Foster’s possibly genuine lack of understatement as a result of linear thinking. Trauma means a bodily wound or an emotional shock that causes lasting side effects. In the show against the day 2008 in Wiels, I developed a body of work that dealt with immediate or virtual imagery. Either derived from striking a pose such as a diptych, Against the Day I and II from the websites still under constructions such as the normal a website specialized in constructing humanoids. Real-time images based on reality TV shows. Or the one image of a hit of a sniper somewhere in Bagdad transmitted by means of a smartphone. The show was about the idea of excavation but one that deals not so much with the archeology of memory but moreover with a definite sense of dystopia where the idea of the trauma merely becomes a means of transportation with an indemnity clause attached to it.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: Let’s stay just a little longer in the horizon of the new image in an environment of construction the digital media. Their feature could be perceived as the visualization of events, technically perfect and the most perverse – very narcissistic that connects the permissive society and its consumer-minded actors. Is it possible your image shift in the direction of so-called figurative painting regarded as a subversion of the concept of the media-created reality? I am thinking primarily on your famous works – political figures and public personalities – as a critique of the ideological dark places in Western civilization: the Holocaust, colonialism, nationalism, and racism.

LUC TUYMANS: Very early in my artistic career I developed a concept, which I entitled authentic forgery. Since it was very clear to me from the start that sheer authenticity was and is an impossibility. Everything is derived from something else. Therefore I restrained myself from making art based on art and decided for the real as a departure point, transforming it to something that could be considered subverted or even stronger perverse. As for the 2nd World War, I took it as a timeslot a history nearest to my own using it as a building block of a sort a certain history of violence. It opens up the possibility of an inquest of the relationship between torture and tenderness.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: Something obscure and uncanny lies in the very core of the idea of banality which taken place in your paintings entitled Still Life 2002. In an interview with Julian Heynen from 2004 on the occasion of the exhibition of paintings in Dusseldorf, you said that “banality becomes larger than life, it’s taken to an impossible extreme”. Why? Is it because the painting has lost its sublime reference point in the era of technology and media, or because the arts should over and over again testify to the disintegration of the meaning of life in the areas of work, leisure, and deathliness?

LUC TUYMANS: This particular painting came about because my wife and I witnessed 9/11 in real-time in NY. At That point I thought it would have been redundant to react to it immediately, therefore I thought of a detour, sort of juxtaposition to the horror by means of portraying something idyllic. I chose the lowest denominator within the format of painting, which is still life or natura morte, and it was made especially for Documenta XI. By blowing up the image, portraying it in a state of elevation, the contrast was reduced, as if the image was projected onto the bigger blueish white backdrop, making it totally obsolete. By making a nearly transparent apolitical painting its undercurrent became highly political, and this makes it an understatement like I mentioned before.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: History painting, the portrait, landscape… Was the idea of painting exhausted after the end of the avant-garde currents in the 20th century in constant search of the shock inside the cruel reality and its aesthetisation process? In the case of neo-Expressionist face investigations during the last thirty years in painting there are, it seems to me, ascending line in escaping the body gestures to display anxious state of human as we have an ordinary example in the paradigmatic works of Lucian Freud. Why instead of iconoclasm the objects in two-dimensional space we have witnessed again the return of the human face as the screen of suffering and indifference?

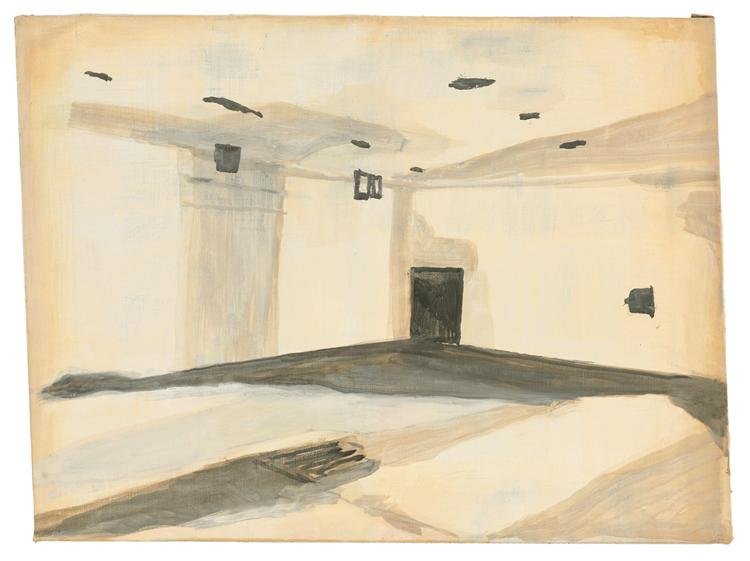

LUC TUYMANS: For a long time I avoided painting humans or portraits restraining myself to space as a void. If a portrait or a face would crop up, it would be derived from objects, dolls, toys, or figurines in a certain setting taken from cropped cutouts of catalogs of dioramas from the miniature modeling railroad magazines. Only from 1992 on I allowed myself to paint portraits based on photographs of real people, but they were based on imagery for medical use from a book called Der diagnostische Blick, from whom medical students should be enabled to make a diagnosis of a disease. This particular body of work is probably the one that comes the closest to an idea of naturalism. By the fact that they are merely symptomatic they totally miss out on the real. To this day a portrait for me is never about the psychology of the portrayed, it’s just a shell, and if the spectator still wants to endear it with his or her emotion that in my case just resonated as collateral damage.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: Your floating abstract composition, as Bloodstains (1993), derived from photographed models, photocopied images, or film stills, has attempt to analyze something between the micro-worlds of uncanny disease (AIDS) and its representation through the indexical sign of image. Could you draw a thin line that separates the impact of quantum data on the physical environment and artistic “reactive proliferation” that matters?

LUC TUYMANS: What was fascinating for me about the microscopic image of blood- stains was that its cellular structure multiplies itself into identical doubles. So apart from the division of the image, there was no real change; it’s sort of renders itself to a certain status quo. An image although so-called, animated moving but kind of incarcerated in its own perpetual modus vivendi. It made sense as it was a logical follow-up to the Diagnostische Blick portraits just again portraying other forms of detachment.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: It’s surely become obvious to entire critics that your most famous works include Orchid (1998). The flower’s bilious greens and muddy browns signify natural and artificial color, growth, and decay. But, what if the natural evolution of the biological species has come to the final stage of reproduction? Image as digital scanning-immersion in the virtual space leads to the ultimate limits of the worlds – reality and hyperreality. Can you tell us just a little bit more about the preoccupation with the relationship of biological currents and death inside the fold of contemporary art, particularly respecting your research?

LUC TUYMANS: Orchid was made because of a newspaper article that stipulated that the gender of plants was disproportionately changing from male to female because of climate change. I, therefore, took the image of an orchid because of its ultimate feminine and sexual connotations. I then covered the image with a nearly chemically toxic foil from which I then made the painting; all this to emphasize the discrepancy between the organic or altered state of things. The painting Orchid was the poster child of a show at Zwirner from 1998 called “Security” which implies insecurity.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: In the catalog entitled Luc Tuymans (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art – Wexner Center for the Arts, 2010) you said very explicitly: “Violence is the only structure underlying my work”. If I could briefly interpret that statement, I would say that the violence here has a double meaning: (1) ontological, or that art is always more involved in the world of power and destruction and (2) an epistemological, or that painting assumes its own self-creation in the mirror of order and chaos. When Walter Benjamin spoke of divine violence it should be regarded as the antinomy of the foundation of the natural law. Without the act of initial crime committed by a sovereign nation-state, there would be no ethical laws. What you really want to perform in the medium of painting on the edge of re-politicization and ethical turnover – compassion, deep insight into societal anomie of global interconnectedness, or overcoming the relationship between the actors of crime and their invisible complicity?

LUC TUYMANS: When asked on numerous occasions why do you still paint my only answer was and still is because I refuse to be naive. The first image being it in a cave was a conceptual one moreover than just informing the happy few how to hunt and to kill. Its deeper meaning was symbolically transferred to them through the idea of the index ending with the iconic image itself. Of course, the image was violent, it couldn’t have been otherwise. I already mentioned a thin line that exists between torture and tenderness – violence more than happiness always had a more lasting impact in terms of bodily mutilation, scarification, or more fear-induced psychological consequences. And as you correctly mentioned in your questionnaire there is a definite relationship between the actors or perpetrators of crime and the idea of invisible complicity.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: Cinema has a strong impact on your paintings, but obviously not as the simple imagery to transport directly on the canvas in all possible genres. Gilles Deleuze has been articulated the main exit from old-fashioned metaphysics which draws the line of bifurcation between movement and time. There are no more images without moving-production in the very core of the camera as technical apparatus, and there are no more images without time-spacing transformations our becoming as desire machines. What’s the meaning of cinema in your artworks (performances, paintings)?

LUC TUYMANS: I wrote a very elaborate text for an art publication De Witte Raaf, it’s translated in English and is included in a publication with a selection of my own writings and others called, On & By Luc Tuymans, co-published by Whitechapel Gallery and MIT Press 2013. The title of the second part of the article “On the Image” was entitled “On the Moving Image” (1996). On a more personal level, the importance of the correlated stance of an image has been very important to me since I’m the product of a television generation. This means the overdose of transmitted images paralleled by an extreme manqué of experience. For me, the fight against the reproducibility of an image or photographs was no longer at hand neither is the fight against new media since it is one we cannot win. Better to incorporate it into the toolbox to then intelligently pause it into the inevitable of the anachronism which painting is. The other similarity is that as a photographer I would always be too late, never at the moment. The film allows you as painting to approach the image one can edit through the lens, one can overpaint a painted surface.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: Belgium, America, and the heritage? As we know, The Heritage VI (1996) represents the inevitable failure of history. What is the price that this painting has to pay to throw off the shackles of the “New Realism”? Could you show closer what’s going on with all that embeddedness in the photographic media-worlds from the perspective of “paranoia”, as you have said on series dedicated to the superficial areas of our daily information lifecycle?

LUC TUYMANS: The embedment of paranoia in the media is a fairly new phenomenon similar to its predecessor suspense. It’s one of the 20th or 21st centuries initialed to relocate or redistribute fear by means of a prophecy. Therefore extremely contagious and effective when combined with the process of image-making or building it becomes downright dangerous. This is why profound distrust against any form or format of an image is requested.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: Finally, in the recent debate on the neo-avant-garde and the visual arts was a tendency to bifurcate two very extreme positions. Those who think that the subversive movement has to be only valued in the museum as many artistic styles from modern history, and those who think that we should continue the straight into events to come without any doubt in the sense of this project. Is it your “faith” in the mission of painting something really out of the current condition?

LUC TUYMANS: History fate and the mission of painting is my current condition.

ŽARKO PAIĆ: Contemporary art as reflexive relationship to your own path has so many traces in close connection to Paul Thek, great American painter, sculptor, and installation artist. In the book Paul Thek – Luc Tuymans: WHY? (Galeria Isabella Czarnowska, Berlin, 2012), we can see a strange dialogue and recognition of spiritual kinship. Why? Why contemporary art is again seeking its roots in myth and sacrifice if everything around us has become perfectly clear, like in a morbid pharmacy where things and conditions are designed according to the criteria of success and market value?

Luc Tuymans

Luc Tuymans is an influential contemporary Belgian artist. Painting from photographs and films, Tuyman’s works examines cultural memory through a muted palette and choppy brushstrokes, lending the paintings an ambiguous meaning. Tuymans deliberately chooses images of historically significant places or people, as seen in his work Lumumba (2000), a portrait depicting the first Prime Minister of the independent nation of Congo. “If you ask people to remember a painting and a photograph, their description of the photograph is far more accurate than that of the painting,” he has explained. “There is a physical element intertwined with the painting. It shakes loose an emotional element within the viewer.” Born in 1958 in Mortsel, Belgium, he studied fine arts at the Sint-Lukasinstituut in Brussels where he first became interested in the work of El Greco. He later attended the Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp, where he mainly focused on video and film. In the mid-1980s, the artist began painting again, making works which broached the subjects of the Holocaust, the Oklahoma City bombings, and the Belgian Congo. Over the following decades, Tuymans has established himself with numerous solo exhibitions around the world. He currently lives and works in Antwerp, Belgium. Today, the artist’s works are held in the collections of the Tate Gallery in London, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst in Ghent, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among others.